In this chapter we consider what interviews are, why they are important, and how to use them successfully. At the end, we look at how to deal with difficult interviewing challenges, especially for radio, TV and online.

______________________________________________________

An interview is a special kind of conversation in journalism. It is a conversation between a journalist and a person who has facts or opinions which are likely to be newsworthy.

News involves people. Whatever news story you are researching, there will be a person or some people who know what you need to know, or who have relevant opinions. They will usually be happy to tell you.

Your job is to find these people, and then ask them what you think your readers, listeners or viewers want to know. Interviews are a bridge between people who want information and the people who know what happens, think they know or have important opinions on issues that arise.

Usually, you will hear about news first and find the details later. You may see something happening; you may hear about it during a social conversation; you may receive a press release telling you about it; you may receive a tip-off from a well-placed friend.

However you first hear about the news, the next step is to find out all the details so that you can write the story. The best way to do this is to interview the right people.

Basic principles of interviewing

Speaking and listening

An interview is just a conversation, although it is a particular kind of conversation. As in any conversation, you and the person you are talking to will both be involved in speaking and in listening. Think, though, about which is more important to you - to speak or to listen?

Of course you will have to speak, to put your questions and explain what you want to know. But the purpose of the interview is to hear what the other person has to say. The most important aspect of an interview is for you to listen to what the person has to say, and to make sure that you understand what he or she is saying.

It may be necessary to ask further questions to clarify what has already been said. For example, you might ask: "Did you say that the building would cost $725,000?" or "Did you mean that the members of the committee would all be sacked?" Try not to interrupt, though. Let the person finish answering first, and make notes of what you don't fully understand. You can ask questions for clarification when it is your turn to speak.

^^back to the top

Making friends

Everybody talks more freely when they are relaxed and they like the person they are talking to. If you want to get the best out of an interview, it is up to you to make sure that your interviewee (the person you are interviewing) feels this way.

For a start, you can try to arrange the interview in an informal setting - over a beer or a meal, in a club, under a tree. Otherwise, interview the person on his or her own territory - their office or home rather than the newspaper office. This will help them to feel at ease.

Then you have to gently take control of the situation, to guide the conversation where you want it to go. How you do this depends upon the person you are interviewing - an angry villager with a grievance which he is not expressing very clearly may need firm guidance; a High Court judge might need very careful and polite handling.

Young journalists in developing countries often find it difficult to take control, especially if they are interviewing somebody with high social status. Women journalists, too, find it very difficult in some cultures to take control if they are interviewing a man.

You cannot disregard the cultural setting in which you live and work, but you should remember that you are striving to be a professional person. Controlling and guiding the interview, to get the relevant information without wasting time, is an important part of your professional skill. And remember, you are not doing this for yourself but for all your readers, viewers or listeners.

It is a good idea to start any interview with friendly questions, even if they are not necessary for the story you wish to write. It will help you to establish a link with the interviewee. You should always look and sound interested in the answers you receive, too. If the interviewee once feels that you are not listening, they will stop bothering to answer your questions.

Save your nasty questions until last. You may have to ask a trade union leader why he has called a strike without consulting his members, or a managing director why he has sacked 25 people and thrown them out of their homes.

If you think that the interviewee will not be happy with the question, make sure you have asked everything else first. Then you can ask the difficult question - if he gets angry and tells you to leave, you have wasted nothing; if he gives you an answer, you might have a better story.

^^back to the top

Visualising

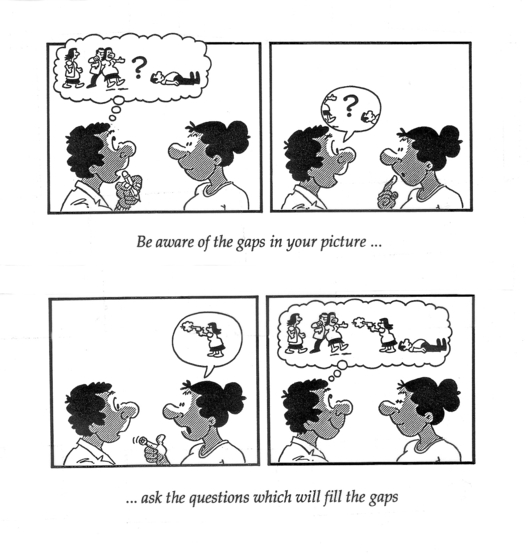

One of the most important skills in interviewing is the skill of visualising.

As the person you are interviewing gives you more pieces of information, you need to add them to the picture you have in your mind.

Can you now visualise the whole story? Could you answer any question about this story if it was put to you - Who? What? Where? When? and especially Why? and How?

If there are any gaps in your understanding, this does not mean that you are at fault - it means that you lack information. Your next question should be to fill in this gap.

Some journalists write down all their questions before they begin an interview, though using them as a script is not usually a good idea. You may write down a few very important questions in advance; but the next question you ask each time will depend on the answer you received to the question before.

Visualise the whole story throughout the interview. Be aware of the gaps in your picture. Ask the questions which will give you the information to fill those gaps.

Sometimes your interviewee will speak in reply to your question, but not answer it. This may be accidental, if they did not understand your question or have lost their train of thought; or it may be deliberate, if they do not want to answer the question, but do not want to say so.

Sometimes your interviewee will speak in reply to your question, but not answer it. This may be accidental, if they did not understand your question or have lost their train of thought; or it may be deliberate, if they do not want to answer the question, but do not want to say so.

Either way, if you ever ask a question and do not receive an answer, you should ask the question again. This does not have to be rude. You may say:

"Thank you, Minister, but I'm not sure that I heard the answer to my question. I was asking you whether you agree with the World Bank recommendations."

The object is to be polite but persistent. If the interviewee does not want to answer a question, make them say so. You can then thank them, move on to the next question ... and include in your story that they declined to answer this question.

^^back to the top

Evaluating

As well as listening and understanding what you hear, you will need to think while you are listening. Ask yourself what is the significance of what you are hearing? Is it a big news story or a small one? Is it news at all? What will be the effect of what you are hearing on people's lives?

In this way you can evaluate what is being said. When you have a picture in your mind of what the news story means, you will know the sort of question to ask next.

^^back to the top

Recording

However good you may think your memory is, you must keep a record of what you are told. An hour later, after a lot more talk and a journey back to the office and a chat with the chief of staff on your way to your desk, your memory of what was actually said may be unclear.

Audio recorder

You may record an interview with an audio recorder. If you are working for radio, you will need to do so, but even some newspaper and magazine reporters work this way. The advantage is that you record the interview accurately, without having to worry about note-taking, and can concentrate on what the person is saying. The disadvantage is that, after the interview, you may have to play the whole recording through again, sorting out what you want to use and what you don't want. This will take more time than glancing through your notes.

If you are recording an interview with an audio recorder, you will need to follow a few simple rules:

- Know your recorder and what all the switches do. Practise with it in the office, until you are familiar with it.

- Check that the battery is fully charged before you leave the office. The best thing is always to put the battery in the charger whenever you finish a job, so that it will be ready for the next job. Consider taking spare batteries if possible, just in case.

- If you are using an old-style tape recorder, take a spare clean tape with you. Keep an eye on the tape recorder during the interview, so that you can change the tape before it reaches the end.

- Place the microphone in a good position to record, and the audio recorder conveniently beside you. Check before you begin the interview that it is working and that the sound levels are right.

- Set the counter to zero at the start of the interview.

Notebook

The alternative is to make notes in a notebook. This can best be done by using shorthand, so that you note the speaker's exact words while he or she is speaking them. You can then use them as a quote later, if you wish.

The advantage of such notes is that you do not bother to take a note of stuff which is boring or irrelevant, and which you know you will not use. Notes are selective and save time later.

For newspaper journalists, this is often the most efficient method. However, you will need shorthand of at least 80 words per minute, and preferably 100 words per minute, if you are to use this method effectively.

For court reporting, this is often the only method of recording allowed in the court.

Combination

Journalists who do not have good shorthand, or who work in a language for which there is no good shorthand system, can use a combination of the previous two systems.

You take an audio recorder to record the whole interview, but you also make notes in a notebook.

There is no need to write down the speaker's words - they will be on audio recording - but you can note when he or she says something interesting. By noting the number on the recorder counter, you will be able to find quickly the bits you want when you return to the office.

So, you may write in your notebook:

Rice project 026

Good quote 041

Cash figures 063

Quote 074

Copra drying 093

Quote 124

V. good quote 138

When you return to the office, you will be able to ignore most of the recording, and fast forward to the bits you want. Rewind the counter to zero. Now, when the tape counter shows 026, you will find the start of the discussion of the rice project; at 041 there is a good quote; and so on.

This has a very important advantage, that you can quote accurately what people say. This method is slower and more cumbersome than just using a notebook; but it is a very good compromise for journalists who do not have shorthand. It will also give you a record if your interviewee objects to how you quote them in a subsequent story.

^^back to the top

The interview formula

Every interview is different, depending on the person you are interviewing and what you are talking about. All the same, there is a formula which you can apply to every interview, which will help you to get the best out of it.

Preparation

Before any interview, you need to do some preparation. Talk to your colleagues and find out whatever they know about your interviewee and the background to the story. Get the cuttings out of the library and read what has been published before or do a search online.

Check on the sort of story that is wanted - is it a hard news story, a background story, or a personality profile? Then make a list of the things which you need to know, so that you can ask the right questions.

Finally, make yourself look neat and tidy. Whether you dress formally or informally depends upon who you are going to interview, but you should always look clean and you should never look scruffy.

Politeness

Nobody is obliged to be interviewed by a journalist, so be grateful and be polite. At the start of every interview, introduce yourself in a clear confident voice - "Good afternoon, Mr Wingti, I'm Joe Vagi of the Niugini Courier. Thank you for agreeing to see me."

Don't be in too much of a hurry to get down to business. Take a minute or two for appropriate small talk. You might ask about his health and his family and how he is settling into his job; this will indicate that you care about him as an individual and will help to establish a rapport. Don't overdo it, though. Remember that he may be a busy man and have better things to do than discuss his family with a total stranger!

It will be a matter for your judgment on each occasion how much of this small talk is appropriate.

Open questions

It may be that you know most of the details of a story, and only need two or three details from an interview. In that case you can get straight to the point. More usually, however, you will have only a sketchy idea of the story. In this case, the ideal first question is something like: "What actually happened?" or "Could you tell me about..?" This will give you the broad outlines of the story.

Avoid asking questions with a yes/no answer especially if you want a recorded interview for radio or television; it makes very dull listening to hear long questions from the journalist and one-word answers from the interviewee. Ask questions which invite details, not agreement or disagreement. Remember, you want to spend most of your time listening, not speaking.

Visualise

Once you have the broad outlines of the story, try to build up a picture in your mind of what happened. If there is any part of the picture which is not clear, ask for clarification. You will want to know Who? What? Where? When? Why? and How?

You must start with the most important areas of the story and gradually fill in the less important detail, because the interview might be brought to an end at any moment.

Don't forget to ask about the past and the future, too - what led up to the story, and what will happen as a result. Try not to interrupt.

Recap

To "recap" is short for "recapitulate". This means to go back over your notes before you let the interview end. Read them through, see if they make sense and check that no details you need are missing. Don't do all this in silence, though, or your interviewee will think you have finished. Keep talking, while most of your mind is on your notes. When you come across names, check the spelling; when there are figures, check that you have them right.

Finally, tell your interviewee what you understand the story to be. This will take time, as you tell back to the interviewee in an orderly form all that he has told you in bits and pieces. If you have got it wrong in any respect, you may be sure that he will stop you and put it right.

The final question

We are all human and fallible, so you may forget to ask something important in an interview. Or there may be something which you could not know about, which will make a good story.

For these reasons, when you have asked everything that you think you need to know, there is one more question to ask: "Is there anything else I should know?"

Before you go

You may find that you get back to your desk after an interview, start to write the story and then realise that you did not ask an important question. You then have to telephone your interviewee and put the question.

Before you leave the interview, therefore, check that you have their phone number and check that they will be available on that phone number for the next hour or two, "in case there are any other questions". If the interviewee is about to go out, try to get a number where you can contact them.

Leave your business card, if you have one, or otherwise a written note of your name, company and phone number, so that the interviewee can phone you if a thought occurs to them after you have gone.

If you think the story needs a photograph, check whether the interviewee will be available to have a picture taken, and if so when would be convenient.

Finally, say "thank you", shake the interviewee's hand (or whatever is usual in your culture) and part as friends or with at least mutual respect - you may well need another interview from the same person at some future date.

Requests to play back an interview

After you finish recording an interview, you may be asked by the interviewee to play it back to them. Unless there is a compelling reason to agree, you should avoid doing it. There are several good reasons for declining their request: it may take considerable time; it will give them the impression that they, rather than you, will edit it to suit them rather than the needs of the story; they may want to cut or change something they dislike, especially things they have said that might be controversial, i.e. newsworthy.

Refuse them politely and reassure them that you will deal with the material fairly and professionally, that they have nothing to fear.

If they are insistent, you can ask which elements of the interview they are concerned about. If those concerns are justified, tell them you will take them into account when you are producing the story ... and then do it. For example, they may have inadvertantly used a negative or double-negative in an answer, implying the opposite of what they had intended. Make a note to yourself to set the record straight or even re-record that answer to clarify the matter.

^^back to the top

Dealing with difficult interviews

The following section is mainly aimed at radio, television and online interviewing, though some of the issues may be relevant to print journalists too.

Providing clarity

Sometimes radio interviewers need to clarify what an interviewee is saying, either because the technical quality of the sound is poor or because what the interviewee says is unclear. This can happen if the interviewee has difficulty expressing themselves – perhaps they have a speech impediment or communications problems – or because they are not able to describe complex issues in words simple enough for ordinary listeners to understand.

These issues can be most problematic in live interviews, when there is no opportunity or time to edit what is said.

On occasions like this, it is the job of the interviewer to provide clarity for listeners.

Research and pre-interview interview

In some of The News Manual chapters on specialist reporting we discuss the requirement for journalists to have at least a basic understanding of the subject area on which they are reporting. Journalists are often “Jack of all trades” – meaning they know little bits about lots of topics – but they are seldom experts in multiple specialist areas. If you have the opportunity, it is often time well spent to do at least some background research into the subject area you are covering. If the issue is controversial, you might also be able to get a briefing from someone you trust in the speciality, a kind of “pre-interview interview”. While you may not need to record this background interview, if your reporting is for a feature or documentary, you might even be able to weave some of it into your final program – as long as you have obtained permission from the “pre-interviewee”.

Clarification during the interview

Once the interview itself has begun, it may be difficult or unwise to pause it so you can clarify something that’s difficult to understand, so you will just have to keep going and adjust your questions and interjections as you go along.

The following is a short extract from an interview with Australia’s then Chief Medical Officer Professor Brendan Murphy conducted by Dr Normal Swan of ABC Radio National in January 2020, at the start of the COVID-19 epidemic. Notice how Swan uses his own scientific knowledge to encourage Professor Murphy to clarify in simpler terms something the professor may have taken for granted in his answers:

Professor Brendan Murphy: The VIDRL lab in Melbourne has developed a test so they could take a day or so before we're absolutely sure with a confirmatory test. But we're gearing up across the country to get much more rapid testing over the next few days.

Norman Swan: I'm assuming that's a blood test rather than a test of the sputum or what have you?

Professor Brendan Murphy: Well yeah, you can actually do PCR on the biological sample, the respiratory sample - that's the main test to confirm the presence of the virus. Serology is not yet being developed.

Norman Swan: So PCR is where you take a tiny genetic sample of RNA or DNA and then you amplify it up to see whether it's got the sequence of the virus?

Professor Brendan Murphy: Correct.

In the full interview, Swan manages to elicit information without making Professor Murphy seem either ignorant or hard to understand. The interview flows like a good conversation, two people exploring a topic, with the interviewer gently controlling the direction it takes and the language presented to ordinary listeners. It helps that Swan is a practicing doctor, but any well-informed journalist can emulate him with enough research and the quickness of mind to recognise when the interviewee says something ordinary people might find difficult to understand.

If you, the journalist, cannot understand what someone says, you cannot communicate their words effectively to your listeners.

Journalists must always pay full attention when conducting an interview, but this is especially important when the interview is difficult, either because of the complexity of the topic, the language of the interviewee or the sound quality.

Interviewees with communications difficulties

While most interviewees will sound articulate, there will come times when you must interview people who have difficulty communicating. This may be because the spoken skills in the language of interview are not very good, because they are unusually nervous being interviewed or because they have physical or psychological difficulties, such as speech impediments or limited IQ. While you are always better choosing an interviewee who is both knowledgeable and a good speaker, sometimes you have to choose someone with poor communications skills, perhaps because that is actually part of the story.

For example, in December 2022, ABC Radio National’s Life Matters program held a talkback on “Dating when you have a disability”. While they could have restricted their callers and studio guests to articulate people or non-disabled advocates, that would have missed out on hearing from people at the very heart of the issue – men and women who have speech difficulties yet wish to date. Indeed, these are the very people whose communications difficulties make dating challenging.

For this program, the ABC presenters used the “feeding back information” techniques mentioned above. If an interviewee could not be fully understood, the interviewer stepped in to summarise what they had said before moving on to the next issue or a follow-up question. Care must be taken not to seem too obvious or condescending, as that would only embarrass the interviewee and the listeners … and scare off other callers with disability.

To avoid doing this, interviewers must develop their skills at precising (summarising) a person’s answer. A precis is a form of reported speech and, as we show in Chapter 8 onwards, turning a person’s actual words into reported speech is a skill journalists need all the time, but when the interview is live-to-air it is important to get the balance right to clarify something without seeming condescending.

Patience

Journalists always need patience - to track down hidden information, to talk people into giving interviews, to let interviewees tell stories at their own pace and to allow them tell you things they need to say that might not get into your final story.

Patience is especially important when interviewing people with speech disabilities. They may have problems finding words, pronouncing them clearly, putting them together or generally communicating the ideas in their heads. Understand that they are trying perhaps harder than people without speech impediments or intellectual disabilities, so admire their effort and find the patience to hear them out.

The ABC interviewer in the program mentioned above shows how to offer patience, not jump too quickly into silences and not to interject when an interviewee is struggling to communicate an idea. By all means assist them in expressing their ideas, but do not rush them. A good interview, like a good conversation, will develop its own pace. Your listeners will accustom themselves to the pace and will be able to concentrate on what people are saying rather than on how they speak.

Speak clearly

Many people with communications difficulties you interview may be better at listening and comprehension than in speaking, but some will not. Some disabilities will involve hearing difficulties, so speak clearly and at a pace the interviewee can understand. That does not necessarily mean asking questions in a slow, exaggerated way – which may embarrass the interviewee and your listeners – but take special care that you speak clearly, preferably in shorter sentences that are simpler to understand. This is good journalism practice anyway. And constantly monitor their answers, tone of voice or hesitancy, to check your questions are being understood. In face-to-face interviews, their expressions will often tell you how well they are comprehending what you ask.

^^back to the top

TO SUMMARISE:

Work out a method of recording interviews which is best for you - audio or video recorder, smartphone, notebook or a combination of them.

In every interview:

- Listen more than you speak. Control the interview gently, but don't interrupt.

- Be polite but persistent.

- Ask open-ended questions; especially avoid questions with "yes/no" answers.

- Visualise the story as it is revealed to you.

- Evaluate the news story as it is revealed to you.

- At the end of the interview, recap what you understand the story to be.

- Communicate clearly with the interviewee.

- Clarify any answers that might be unclear.

This is the end of the first part of this two-part section on interviewing. If you now want to read on, follow this link to the second section, Chapter 17: Telephone interviews

^^back to the top